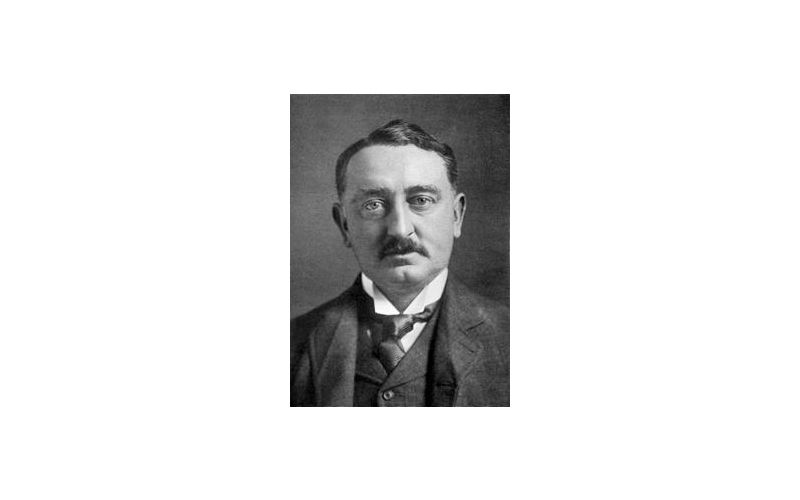

100 Heroes: Cecil Rhodes

The problematic gay man who helped build the British Empire.

Cecil John Rhodes was a British businessman, statesman, imperialist, mining magnate, and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

Hero is probably the wrong word for Rhodes. He certainly played a role in shaping the world as we know it today, but he is a highly problematic figure.

An ardent believer in British imperialism and white supremacy, Rhodes and his British South Africa Company founded the southern African territory of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia), which the company named after him in 1895. South Africa’s Rhodes University is also named after him. Rhodes set up the provisions of the Rhodes Scholarship, which is funded by his estate. He also put much effort towards his vision of a Cape to Cairo Railway through British territory.

He entered the diamond trade at Kimberley in 1871, when he was 18, and over the next two decades gained near-complete domination of the world diamond market. His De Beers diamond company, formed in 1888, retains its prominence into the 21st century. Rhodes entered the Cape Parliament at the age of 27 in 1880, and a decade later became Prime Minister. After overseeing the formation of Rhodesia during the early 1890s, he was forced to resign as Prime Minister in 1896 after the disastrous Jameson Raid, an unauthorised attack on Paul Kruger’s South African Republic (or Transvaal).

Early life

Rhodes was born in 1853 in Bishop’s Stortford in England.

He was sent to South Africa by his family when he was 17 years old in the hope that the climate might improve his health – he suffered from asthma.

Diamonds

In October 1871, 18-year-old Rhodes and his 26-year-old brother Herbert left Natal for the diamond fields of Kimberley in Northern Cape Province. Financed by N M Rothschild & Sons, Rhodes succeeded over the next 17 years in buying up all the smaller diamond mining operations in the Kimberley area.

Politics

Having secured a seat in the Cape House of Assembly in 1880, Rhodes became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony in 1890.

Rhodes was one of the key architects of moves to disenfranchise black people in the Cape – limiting the amount of land which black Africans were legally allowed to hold and increasing the property qualifications required to register to vote.

Rhodes was forced to resign as Prime Minister in 1895, following a failed raid on Transvaal.

British South Africa Company

Rhodes promoted his business interests in southern Africa as being in the strategic interest of Britain – preventing the Portuguese, the Germans or the Boers from moving into south-central Africa.

In 1889, Rhodes obtained a charter from the British Government for his British South Africa Company (BSAC) to rule, police, and make new treaties and concessions from the Limpopo River to the great lakes of Central Africa. He obtained further concessions and treaties north of the Zambezi, such as those in Barotseland, and in the Lake Mweru area.

By the end of 1894, the territories over which the BSAC had concessions or treaties, collectively called “Zambesia” after the Zambezi River flowing through the middle, comprised an area of 1,143,000 km2 between the Limpopo River and Lake Tanganyika. In May 1895, its name was officially changed to “Rhodesia”, reflecting Rhodes’s popularity among settlers who had been using the name informally since 1891. The designation Southern Rhodesia was officially adopted in 1898 for the part south of the Zambezi, which later became Zimbabwe; and the designations North-Western and North-Eastern Rhodesia were used from 1895 for the territory which later became Northern Rhodesia, then Zambia.

Rhodes was a white supremacist. He wanted to make the British Empire a superpower that dominated the world.

Personal life

Rhodes never married.

Historians suggest that he was a gay man, in a relationship with Neville Pickering – his private secretary.

Rhodes made Pickering the sole beneficiary of his will, but an accident resulted in Pickering catching septicaemia, during which time Rhodes spent six weeks trying to nurse Pickering back to health. Pickering eventually died in Rhodes’ arms.

Rhodes died of heart failure in 1902, aged 48.

In his Will, Rhodes provided for the establishment of the Rhodes Scholarship – an international study programme.